Does Susan Sontag’s book

‘On Photography’ still hold any relevance today with the modern-day photographer?

Samuel Ernest Wright

Student ID: 1449251

BA (Hons) Graphic Design and Digital Communication

Year 3

Word count: 6,265

Table of Contents

List of Illustrations

1. Introduction

2. Camera History

3. Finding Beauty

4. The Eye of the Beholder

5. The Holiday Photographer

6. Eastern Photography

7. Film vs Digital

8. Conclusion

9. Bibliography

List of Illustrations

Fig.1 100photographs. View from the Window at Le Gras

Online. Available from: https://100photos.time.com [Accessed December 2019]

Fig.2 Wikipedia. You Press the Button, We Do the Rest

Online. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org [Accessed January 2020]

Fig.3 Smalltowninertia. MARKET TOWN : TILNEY1 : WATCHING A PLANE FALL FROM THE SKY, AFLAME.

Online. Available from: https://smalltowninertia.co.uk [Accessed December 2019]

1. Introduction

Susan Sontag wrote the book ‘On Photography’ in 1977 when 35mm film was the basis

for all photographs in this period, there were some exceptions, but these were only accessible to the very wealthy. In 2020, 43 years later, 35mm photography as a format is barely surviving. We are in the height of the digital age. But do her theories and opinions still hold any relevance? This is what I will be discussing in this essay. As we now live in the digital age, it is even easier for the ordinary person to take a picture in all aspects of their lives and share it with the rest of the world. It seems to me that people are using photography more than ever for recognition, approval and clarification. More now, than when Sontag wrote her book, people are becoming ever more reliant on their cameras and smartphones, some even using images to make money daily. This essay is built up

of seven different sections, with the first being a secondary introduction to photography, briefly going through the history of photography and the development of cameras over time, from when it first started to present day. The next five sections explore the main 5 ideas of Susan Sontag that particularly interested me. These include ‘Finding Beauty’, which talks about why people take photographs, ‘The eye of the beholder,’ which links

to the previous section, but explores in greater depth peoples perspectives of what is beautiful, and why people photograph certain things. In the third and fourth sections I put forward the concept of ‘The holiday photographer,’ and the differences between Eastern and Western photographic culture. In both sections I will discuss and compare Sontag’s views and opinions with my own, supported by evidence from today’s society. I also show how in today’s society we continue to overuse the camera, taking away from the moment. In the final section, ‘Film vs Digital,’ I discuss the advantages and disadvantages of both types of media and compare how more advanced the digital camera is now in comparison to when Sontag wrote her book. I will then summarise my findings and thoughts

in a conclusion.

2. Camera History

The concept of the camera has been around since the late 18th century, made possible

by two critical principles. The camera obscurer image projection, and the observation that some substances are visibly altered by exposure to light. Although it was around 1717 that Johann Heinrich Schulze captured the shapes of letters on a bottle filled with a light-sensitive liquid, it was not until a century later that Joseph Nicephore Niece managed

to fix an image that was captured with a camera. ‘View from the Window at Le Gras

is the earliest surviving photograph taken by Joseph Nicephore Niepce dating back to 1826 (Fig.1). Its exposure time is said to have lasted around 8 hours but could have taken many days. In 1839 Louis Daguerre pushed the photographic process into the 19th century by inventing the technique known as the daguerreotype process. This process, unlike its predecessors, used a highly polished silver plate with wet chemicals poured onto the surface to take a photograph. This was the first publicly announced and commercially practical photographic process. Its success was due to the fact that it only required minutes to expose instead of hours. This process led to what is now considered to be the of the birth date of photography.

Fig.1, View from the Window at Le Gras

Although the daguerreotype could be used commercially with success only one exposure/ print could be made of the subject. In 1841 a new process was developed by Henry Fox Talbot. This process was known as a calotype which used a light-sensitive paper. Just like the daguerreotype, exposure times only took minutes, but, after the exposure a negative of the subject was produced, which could then be used for reproducing multiple prints of the same exposure. People over time have taken the calotype process and perfected it so that the everyday consumer can use it. This would be the basis for modern photography as we know it today.

It is widely believed that roll film was invented by the Eastman Kodak Company, founded in 1888 by George Eastman, a company we now know as Kodak, however, this is not the case. It was invented by two farmers, Peter Houston and his brother, David Houston. In 1855, 5 years after Eastman and his partner Henry A. Strong began producing dry plates, Eastman discovered this invention, bought the license and patented it, thus, started producing 120 roll film. In 1888 the first Kodak camera came onto the market, it carried enough film to take around 100 exposures. This invention of the Kodak camera marked the birth of the amateur photographer as now the everyday person could afford to take photos. In the company’s advertisement campaign the slogan ‘you press the button, we do the rest was used.

Fig.2, Kodak camera advertisement from 1888

Although the 120 roll film made photography easier to handle and brought it to the masses it was big and not particularly portable. This is why the creation of the 35mm film which evolved in the late 19th century was so revolutionary. William Kennedy Laurie Dickson sliced 70mm Kodak motion picture film in half and spliced the ends together. After 35mm film was invented many inventors tried to use it for still imagery and in 1908, a patent for a 35mm camera was issued to Baradat in England, however, this camera was never produced or sold. The first 35mm camera to be produced was, in fact, the Jules Richard’s Homeos camera, which was first sold in 1913 and continued to be produced until 1920. Although using 35mm film was easier it was only available to the wealthy, as cameras using this film were very expensive. This was sadly the truth until, in 1936, when the Argus A was introduced. Following this many more were developed allowing the amateur photographer access to the world of 35mm film. This still did not dominate the film market until the 1950’s but has since become the most popular film to date.

Since the birth of photography there has been a desire to produce colour images. In the late 19th century the challenge began to invent a film like Henry Fox Talbot’s, only one that could be exposed and take in the three colours of the light spectrum; cyan, magenta and yellow. Products were available between the 1890’s and the 1950’s but came with a hefty price. When speaking to my grandad a keen amateur photographer from the 1950’s onwards, he mentioned that he was only able to afford one colour roll of film a year due to it being several times more expensive to buy. Compared with black and white film, colour still had a few setbacks with the requirement of a flashbulb when taking images indoors. It wasn’t till the 1970’s that prices dropped, film sensitivity improved and electronic flash units replaced flashbulbs. It is since then that for most families colour has become the normal medium. This would have been the film in which Sontag would have been using at the time she wrote her book, On Photography. From looking at the history leading up to this point, she could clearly understand and make predictions on where photography was heading.

Film continued to boom throughout the 1970’s, 80’s and 90’s with different film camera crazes being born like the Nimslo 3D camera which allowed the viewer to see the image with a stereoscopic/reallife view, the flat disc camera which was introduced in 1982 by Kodak, was a smaller 10mm x 8mm film size which allowed the camera to be smaller and easier to handle. These types of cameras where not for the serious photographer but for the consumer, the disc camera was targeted at the amateur photographer. Although the consumer cameras were fun and quirky they were still no match for a SLR 35mm film camera, this continued to dominate use until a transition period around 1995–2005 in which the digital camera became more widely available to the consumer due to it becoming less expensive.

Over the next ten year period film is pushed into a niche market. Major camera brands such as Nikon and Canon converted to digital, with the digital sensor in the newer cameras being smaller the rise of the compact cameras came to power, half the size of the film camera, easier to use, recording video also, the consumer flocked to this new development. Another transition period arose between 2010 and 2016, due to camera sensor sizes forever being halved in size and picture quality not being effected, this was then implemented into phones. Over 6 years the growth of the smartphone rose and with it the camera as well, people didn’t need to carry a phone and a camera but just one now.

In 2007 the Apple iPhone 1 was released to the world with a built-in 2.0-megapixel camera. Although this was not the first mobile phone to have a camera built-in it marks the start of the phone camera war. Since this date, Apple, Sony, Samsung and many more companies have fought to dominate the camera phone market, this war still rages today in 2020. Apple have now released the iPhone 11 pro boasting a 12-megapixel camera with wide and telephoto lens built-in, making it even more easier for the consumer to take images today

By knowing the evolution of the camera it allows me to see clearly the changes from the beginning of photography to when Sontag was writing and its further development to now. This will allow me to discuss the relevance of Sontag’s book in relation to today’s digital age and its ever-expanding uses of technology, creating an entirely new generation to the one Sontag knew. Some of Sontag’s assumptions on future photography have come true during my lifetime, thus showing her relevance even further.

3. Finding Beauty

One way in which ‘On Photography,’ still holds relevance with today’s modern photographer is through the aspect of finding beauty. Sontag states that ‘What moves people to take photographs is finding something beautiful.’ This can be seen not just over the 43 years between 1977 and 2020 but throughout the whole of photographic history. Since the invention of the camera, people have wanted an idealised image of themselves, they have wanted to find the beauty that one possesses. ‘Many people are anxious when they’re about to be photographed: not because they fear, as primitives do, being violated but because they fear the camera’s disapproval.’ People want a photograph of themselves looking their best, they want to produce an ideal image of themselves to give them reassurance and confidence. To be self-approving. They feel ‘rebuked when the camera doesn’t return an image of themselves as more attractive than they really are.’ However, in reality, few are lucky enough to be “photogenic”—that is, to look better in photographs, ‘even when not made up or flattered by the lighting, than in real life.’

Sontag speaks about this in the 1970‘s, but even when we fast forward to 2020 it is still happening, only this time, on a colossal scale. Being an amateur photographer myself I have been asked to take portraits of people and their families. Once the tripod, lights and finally the camera are all set up it is then down to the subjects to get into formation and pose for the photograph. Whilst watching this debacle take place, I analysed and stereotyped their positions and stances and came to the conclusion that all of them were trying to look like their idealistic versions of themselves. It is interesting to watch how the many different types of people and age groups react. On the occasion of a boy’s 18th birthday party I noticed how the boys straightened up and broadened their shoulders to make themselves look bigger and bulkier, to make themselves look more like society’s idealistic image of a man. I have also noticed that most girls use a side pose to show off their figures. Girls tend to breathe in to make their stomach look smaller and chest bigger, giving them that idealistic hour-glass figure. Both parties want to look ‘beautiful,’ or at least want to look like what society tells them is beautiful. It is a very strange thing to watch as a photographer because you witness the person before the photo is taken and then afterwards. In some cases the person can make themselves look very different from what they really look like. For a few their confidence also seems to be heightened after looking at the photographs, which indicates to me just how much people rely upon images in today’s world. As Sontag discussed, ‘We learn to see ourselves photographically, to regard oneself as attractive is, precisely, to judge that one would look good in a photograph.’ Further supporting the view that people rely on an image of themselves to gain gratification.

The most common and convenient way of getting an idealised image of oneself is by using the phone camera. In 2020 mobile phones are a way of life. Our entire world seems to be concealed in a tiny sim, that is always in our hand or pocket. People use these to take pictures of family events, nights out and everyday living. Most of these images are then uploaded onto a social media platform for others to then see and approve. In today’s society even newly born babies are introduced to images of themselves via their parents’ phones and social media and children as young as 7 are getting smartphones as gifts. This gives birth to the rather dangerous and backwards idea that you need a phone to be cool and a social media account to be socially acceptable. This means that even young children are being exposed to the idea of beauty and the idealised image, leading to this continuing circle of wanting to look better than you perhaps do in real life.

One way in which an idealised photo is achieved is by editing the photo to conceal the ‘non-beautiful’ elements. This is considered to be a ‘fake’ photograph. A fake photograph is ‘one which has been retouched or tampered with, or whose caption is false.’

This falsifying of reality is often used by celebrities to make themselves look more desirable and to avoid any nasty comments. However, techniques such as photoshop and airbrushing are also used heavily within the fashion industry. Surrounding the fashion industry is this term of beauty. What is considered to be superficially beautiful, that is looking good on the outside. However, what is beauty? Is there a unique definition of what beautiful is? When something or someone is beautiful they are said to be ‘pleasing the senses or mind aesthetically.’ When reading this, it bought to my attention that there is no true definition of what beauty is. Therefore, no matter how much people and industries try to impose an idealised image of what is it to be beautiful, and no matter how much editing is used on an image, it will never be 100% ideal or beautiful as beauty is in the eye of the beholder, meaning what some people may find beautiful,

others do not.

4. The eye of the beholder

As mentioned earlier, Sontag draws our attention to the idea of beauty as the single motivation of taking a photograph. This prompted me to look more closely on what beauty is and what it means to a modern-day photographer. Beauty is everywhere.

It is around us constantly. Even if we do not see it, ‘each precise object or condition or combination or process exhibits a beauty’ The phrase ‘Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, is a well-known phrase used by many people all over the world, believed to originate, in the form we know today, from Margaret Wolfe Hungerford’s book, Molly Bawn. Written in 1878, this phrase is a way of explaining that beauty is subjective. In other words it is down to the individual to decide whether an object is beautiful or not. In the same way Sontag is suggesting that it is up to the individual to decide whether or not to take a photograph of something. Is it beautiful to them and will this beauty be captured effectively by a photograph? This is very clear in the art world when you look at the variety of topics each photographer captures, they are all so unique and different. From the angle the picture was taken from, to its colour and subject matter photographs can express an opinion so vividly. In our everyday lives it is very easy to see the subjective nature of beauty when you look at different friendships and relationships; different people find different people attractive. However, many would argue that beauty does not need to always be defined by the external look of things but instead internally. Leaving the question, is beauty that subjective?

On researching further into this concept of beauty I came across a philosopher called Immanuel Kant. His unique uptake on what it is to be beautiful changed the way people looked at photography and art. In the same way I believe that Kant and Sontag both show relevance today by their thoughts on beauty, even though they ultimately differ. Kant argues that beauty lies within the object itself rather than the person viewing the object and although at first difficult to comprehend, on reading Dr Matthew Bowman’s lecture ‘Having words with the visual’ where he explains Kant’s theories on beauty and the sublime, it soon becomes clear what Kant is trying to say. Unlike the majority of people, Kant believes that beauty is not subjective, instead, he argues that when a person says something is beautiful they are expressing this on behalf of a community; they are a universal voice. In other words it is not just their own opinion, ‘But if he proclaims something to be beautiful, then he requires the same liking from others; he then judges not just for himself but for everyone, and speaks of beauty as if it were a property of things.’ Kant clearly believes that something can only be beautiful if many people agree

it is beautiful, otherwise, saying it is beautiful, to Kant, would be ridiculous. Kant then goes even further by discussing how we deem something to be beautiful and whether our reasons are legitimate or not. He discusses the term ‘aesthetic judgement,’ which is a sensory judgement evoked by a particular feeling we have for an object. He discusses how, if we look at a photograph and it makes us feel happy then we may say it is beautiful, however, he also determines that whether we find it beautiful or not may be conditioned by our attitudes towards a certain event, practice or religion. Take for example a picture of the Colosseum in Rome, some may say it is not beautiful because of all the amount of people that died there and the animals that were slaughtered as well as the slaves that built it. To Kant this is not an aesthetic judgement but a moral judgement. People deem it as ugly because of the horrid events that occurred there.

Kant also refers to the fact that some things which to many are externally ugly may still be beautiful to some. For example, too many old abandoned ruins and buildings are ugly eyesores that need to be knocked down with something new built in its place. Yet, over social media are eye-opening photographs of abandoned places. I thoroughly enjoy capturing the unique beauty of these un-used places. It makes me think about what it used to be, what was done there and who was there. The peeling and cracking paint, the graffiti, the rusting steel frames, the birds that nest in the open and falling apart roofs and the silence of the place all add to the overall beauty of the space. Although this is not typically seen to be beautiful, in my opinion and other ‘abandonment photographers’ opinions this is all part of the beauty of life. This clearly proves Sontag’s words on finding beauty to be true and therefore still relevant today.

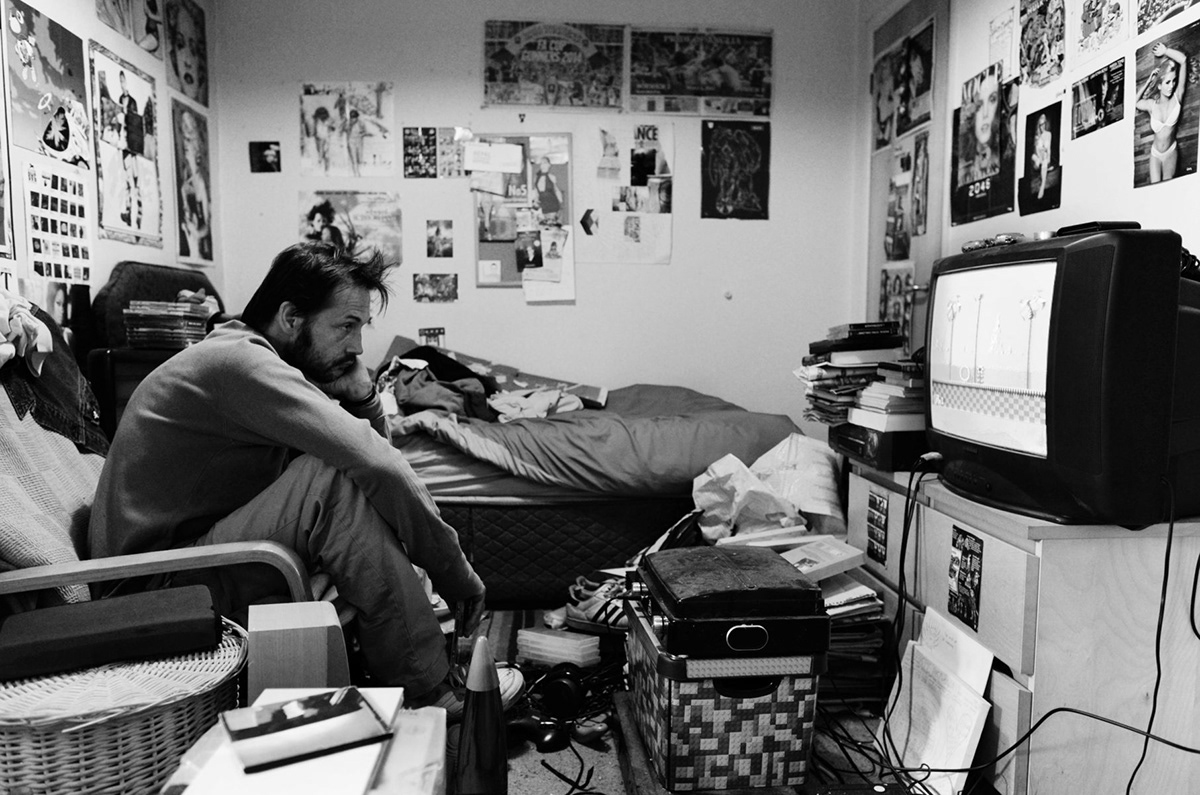

Other photographers such as Jim Mortram take what is deemed as ugly and highlight its beautiful aspect (Fig.3). For example, he uses black and white photography to create soft lines on people who are considered ugly by society: Particularly vulnerable people who live alone and on benefits. These people are often forgotten and thrown to one side, they are never considered to be beautiful. However, Mortram has given us a new way of looking at them, a way of seeing their beauty. When looking at the work of Mortram, it highlighted to me even further what Kant was trying to say. Here I speak of what society deems as ugly, a community, a ‘universal voice.’ Clearly, Kant was also correct when he said that beauty is universal, as there seems to be an unspoken rule of what is and what isn’t beautiful.

Both types of photography relate closely back to Susan Sontag’s words on finding beauty. I and photographers such as Mortram have been moved to take photographs by finding something of beauty. Although this idea of beauty is largely different it is clear that it does not matter. The people behind the photograph have found something in which they deem to be beautiful, something that they can take away with them and treasure. To Sontag it does not seem to matter whether everyone finds it beautiful or not as long as it is enjoyed by the photographer, unlike Kant who says that beauty is objective.

Fig.3, Unnamed man with mental illness watches TV

5. The holiday photographer

Another way in which the aspect of finding beauty is still relevant for today’s modern photographer is through the beauty of scenery. The second most common form of photographs on social media is holiday pictures. The popular holiday snap is quick and easy, it is not thought about or considered in the sense of how a professional photographer would. Millions of us enjoy multiple holidays a year from short weekend breaks to month-long trips travelling across many countries. People are obsessed with taking photos of their time away and broadcasting it to the world or storing their many hundreds of images captured on a phone or computer.

The idea that when you go on holiday you have to take photos of everywhere you go to show people where you have been, what your food looked like, the hotel room, etc, to me seems ridiculous even though to many this constant blog of their day is almost a way of life. This is made even easier today by social media platforms like Snapchat and Instagram where you can upload videos and live streams. This would not have been the case when Sontag was writing her book as smartphones were not invented and photos were not instant. This is why I believe that the motivation for taking photographs on holiday has changed dramatically as it is no longer used solely to look back on great times as John Urray says, ‘Through photographs, tourist strive to make fleeting gazes last longer,’but instead to show off to the people back home and in some cases make a living out of it.

A photograph is a moment in time, a memory made to keep for the rest of your life. Both Sontag and Urry agree that holiday photography is used to transport people back to where the photo was taken; back to the great holiday they had. They both agree that photographs are used as evidence that a person has been on holiday, as it says in ‘The Tourist Gaze’, ‘A photograph thus furnishes evidence that someone really was there...that the mountain was that big...that the culture was picturesque.’

However, as mentioned previously when both Sontag and Urry were writing their opinions down, social media was either not around or was not at the height it is today. Therefore, although what they say is still relevant as many do take photos for that reason, many new motivations have come into play. One in particular which is very new is the idea of a ‘social media influencer’. They use holiday snaps to promote brands and show their lavish lifestyles off to the world. This was not the case in the late 70s or even in 2011 when the third edition of Urry’s book was published.

Nowadays, we come away from our holidays with hundreds of photos to look at when we are back home, however, do we take in the memory when it is actually happening or are we too busy capturing the moment on our phones or cameras? A survey by Jurys Inn has found that Brits on holiday spend an average of 8 hours and 45 minutes on their smartphone or tablet per day.

I feel that this is stopping the person from actually taking in that moment, it is allowing the camera to do the work for you. You no longer have to remember what happened on holiday because you can be prompted by your pictures, not by memory. Susan Sontag suggests, ‘Needing to have reality confirmed and experience enhanced by photographs is an aesthetic consumerism to which everyone is now addicted’

This is even more relevant today as cameras and smartphones with good cameras are easily accessible to the masses. Everyone no matter what generation seems to be entirely dependent on them.

With the phone camera becoming the main basis for photo taking in 2020, with its ever-increasing capabilities, the user can now switch easily between camera and video mode. The video has risen in popularity as it is an accurate visual representation of what happened at the time of the recording, whereas an image is just a snippet of time. Sontag suggests ‘Photographs may be more memorable than moving image’s, because they are a neat slice of time, not a flow.’ I feel that although this quote is true, as images often trigger a memory, in 2020 it is not as relevant because now we have become more reliant on the capabilities of technologies, we find it more easy to remember things if we have a live flow of events at the touch of a button. Most people that I know today take videos as it creates a better memory, they feel it is more accurate. I can see where Sontag is coming from as a still image can trigger a memory and from that a mental video is left playing in your mind of what happened in the particular moment in time and this can stay with you forever, it won’t get accidentally deleted or lost as it’s in your mind. The advantage and yet also a disadvantage with a video is that you don't have to remember all of the details as they are already there for you to watch whenever you would like. Like I said in an earlier section, taking videos is also another way to show everyone where you have been and what you have done. It is yet another way that our generation can show off and share with everyone at a simple click of a button. Another analysis that Sontag makes is that ‘Photography has become one of the principal devices for experiencing something. This theory can be supported by the example of ‘Instatours.’ The website www.instatours.uk advertises tours of major cities such as London, but with a difference. Instead of talking you through the vast history there is to offer, these tour guides will happily become your own personal, professional photographers, helping you to get that all-important ‘holiday snap’ for your Instagram. This tour will set the customer back £120 to £230 and will take between 2-6 hours. This supports the fact that we have become addicted to capturing moments on our cameras rather than store them in our own memory; therefore not only showing the relevance of Sontag’s book but also proving her comments to be true.

6. Eastern photography

Remaining on the subject of tourist photography, Sontag continues throughout her book to mention the overuse of the camera. She mentions how the more photographs we take, the more we need to fulfil our appetite for them. This consumeristic trait only adds to the overuse of photography and its metamorphism from a fine art to everyday action. This can be seen very clearly in tourist photography, which Sontag mentions. In particular, she mentions Eastern culture and the ever-growing photography scene they have. This was only just beginning in 1977 when Sontag’s book was first published and is even more relevant today, when the tourism sector is at an all-time high. We as consumerists are quickly ‘becoming a planet of tourists,’ and according to Adam Majendie ‘Nowhere is this revolution more dramatic than in Asia.’ Sontag discusses the use of photography in Eastern culture and its similarities and differences with Western photography, particularly in the area of motivations for taking photos and their uses. ‘In china taking pictures is a ritual, it always involves posing and necessarily, consent,’ this is still relevant today as I witnessed this first hand on a holiday last year when I went to the city of Edinburgh. Whilst there I visited the historic castle and noticed that there were a lot of tourists. I also noticed how people were taking fancy shots of each other with scarfs brought from nearby shops, oblivious to what was going on around them. People were having to walk around them to get out of the way, but even by this, they were not phased at all. Unlike myself who will randomly take photographs of my family looking at something without their knowledge to get a more natural shot, asian tourists did not. Every photograph was someone posing, no matter whether it was of the castle or the view of the city around it, there was always a person posing at the centre of the photo, again proving the relevance of Sontag’s words. The second experience was again in Edinburgh 3 days later when visiting Calton Hill, which is the opposite side of the city, this gives the viewer, once at the top, a 360 view of Edinburgh and surrounding views of the country of Scotland. Again a large number of Asian tourists were present and taking an abundance of photos. It was here where I sat on a bench and just looked at the view while a group of six Chinese ladies were climbing on one of the monuments taking photos of each other in flamboyant poses. Again showing the relevance of Sontag’s thoughts in her book ‘On Photography’.

In Britain now we have a stereotype of the Chinese tourist; that they take photos of everything, however, I’m sure this was the case when far away on holiday to exotic places with new and exciting culture, became easily accessible in Britain. Chinese tourism has seen a major boom in the last few decades according to the ‘United Nations World Tourism Organisation’ and this to me shows the reasons behind this photography boom. People want to send home proof that they have been to a certain place and show off to friends and family. This is true with both Eastern and Western photography. A difference I have noticed between what Sontag speaks of in her book and now is that the Eastern culture has expanded their photographic creativity. Sontag says, ’more is said with photographs in the West than in China today.’ However, I do not think this is true in today’s society. Although still different from Western photography, I see their tourism photography as very expressive and informative. In some ways their dramatic poses are a form of art in itself but they also express the views of their nation. Chinese fashion is very dramatic, their cities vibrant and colourful and I think this is shown in their poses. Therefore, although what Sontag suggests about Chinese photography is still relevant it also now relevant to surrounding Asian countries also, showing that some of what she has said has evolved over the last few decades, showing just how far photography has come since she wrote her book.

Western and Eastern culture is completely and utterly obsessed with photography and holiday pictures and both clearly overuse photography. I find it sad that both cultures seem to only see things through their camera lenses and not truly with their own eyes, which to me seems to be the overriding opinion of Sontag throughout her book.

7. Film vs Digital

In the time Sontag’s book On Photography was being written, the digital camera was in its very early stages of development. 35mm film was the primary way of taking photos but was limited to 24 and 36 exposures per film and unless you carried around multiple rolls of film, which, when on holiday you may not have wanted to, you would run out. Digital today, on the other hand, allows the user to take as many images as they want or what the camera and phone storage will allow. With digital storage being small it is so easy now to carry extra memory cards so you can take more photos on your camera and the use of ‘The Cloud’ storage capabilities also allows you to take many photos on your smartphone without running out of storage.

With digital being more convenient we end up with a mass of photos either stored on our phones, memory cards, or computers that we never look at again, unless we need to look at them for posting on social media etc. With 35mm, on the other hand, the film had to be developed and prints made in hard copy for the viewer to see them, at this point it was the first time the photographer had seen the images, whereas with digital photography it is instant and corrections can be made. As Urry continues, ‘it has become a ritual to examine the digital camera screen after every single shot.’ I feel that when Sontag wrote her book, photographs were more treasured as they were limited. Photographs had to be developed which cost money and so each photograph taken had to be carefully considered and perfectly executed. This is why I prefer 35mm film as you do not know what you are going to see when the shop assistant hands the prints and negatives over the counter to you. Once paid for, you leave the shop and stand outside hoping that they have came out all right. It’s that moment of either extreme disappointment or smiles of happiness that makes photography so exciting. This is when the memories come flooding back as it can take up to a month may be to use up a film and the memory is forgotten but within that few seconds they come back. This is quite unlike digital where the memory is there for a few weeks whilst it is still on your phone or your computer desktop but sometime after that they fade and become lost within the computer.

Following on from this I think humans take for granted the use of photography nowadays. Nearly two hundred years ago there was no such thing as photography and the self-portrait was merely an artist’s interpretation of what a person looked like. Sontag mentions, ‘Now all adults can know exactly how they and their parents and grandparents looked as children–a knowledge not available to anyone before the invention of cameras,’

This resonates with a modern photographer like myself as I can look back four generations and see what my family looked like right up back to 1901 when my Great Grandad was born. This useful concept of photography is even more poignant today as families who live miles away from each other can rapidly send up to date photos of themselves thanks to the invention of digital photography and the evolving technology of today. This clearly shows that although the type of photograph was different when Sontag was writing, many of her opinions and reflections are true today, proving her book on photography to still be relevant. It is unfortunate that she is not around now to see this for herself or experience digital photography.

8. Conclusion

By looking at the different aspects of Sontag’s book ‘On Photography’ and pin-pointing the cases that really spoke out to me, I have seen clearly that her book is still very relevant to a modern-day photographer. Even though the type of cameras used and the reasons for taking photos has dramatically evolved, not all things have changed. Photographers still photograph things which to them are beautiful, whether that be objectively or subjectively and holidaymakers are still using photography as a means of remembering rather than just taking in the view. Sontag could see the beginning of what we now see as normal everyday life, only to her it is not as simple as a positive evolution. Instead, although gaining more in technological experiences, we are missing out on the world around us. In the final pages of her book, Sontag warns that our humanity is at risk of being dulled by the intensifying technology, and she was right. We have become a nation where images really do ‘consume reality.’

9. Bibliography

Books

Sontag, S. On Photography (England: Clays Ltd, 1978).

Hungerford, W, M. Molly Bawn (England, Tauchnitz, 1878)

Urry, J. and Larsen, J. The Tourist Gaze 3.0 (London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2011)

Online

100photographs. View from the Window at Le Gras

Online. Available from: https://100photos.time.com [Accessed December 2019]

Theoldtimey. History of the 35mm: The Original Compact Camera

Online. Available from https://theoldtimey.com [Accessed December 2019]

Lexico. Definition of beautiful in English

Online. Available from https://www.lexico.com [Accessed December 2019]

Google Books. Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass

Online. Available from https://books.google.co.uk [Accessed December 2019]

Express. Brits on holiday spend almost NINE hours on their smart phones PER DAY

Online. Available from https://www.express.co.uk [Accessed December 2019]

Bloomberg. Chinese Tourists Are Taking Over the Earth, One Selfie at a Time

Online. Available from https://www.bloomberg.com [Accessed January 2020]

Other sources

Bowman, M. Having Words with the Visual: Aesthetic and Criticism